It’s strange how life’s roads diverge (and not always “in a yellow wood”); yet, sometimes, then cross, run in parallel, until they meet again at some glistening, memorable moment. I have known (of) Martin Roscoe (above), on and off, for most of my life. In fact, many years ago, I was the choirmaster of the church near-enough-next-door to where he lived – his prodigious practising forming a wonderful, intermittent soundtrack to my Friday nights: trekking to the same pub with the adults of the choir, that he would later also retire to. We once even played the same piano in the same concert (but, sadly – from my perspective – not simultaneously…)! And I have thus admired him from afar; and occasionally bumped into him at his recitals.

I also met Peter Maxwell Davies – always ‘Max’ – many times: initially when he was leading The Fires of London. And, again, I would “bump into him” now and again. When I was a young musician, he was extremely generous with his time: those vivid inquisitive eyes twinkling acutely as he demanded to know more about my life, my experiences, my compositions. He was a great man; a good bloke… – as well as one of our greatest composers… – and there are many who already miss him sorely. Including me.

Many of these paths therefore lead back to the RNCM: where Max and Martin (and Peter Donohoe) were students; where I spent a lot of time when much younger; and where some of my greatest musical mentors happened to teach. Some of these paths therefore lead to last night: when Martin – after a masterclass in playing Mozart, accompanied by the Orchestra of the Swan – returned to the stage and played Max’s Farewell to Stromness.

I used to sob gently, simply trying to perform this. So I held my hands in prayer; bowed my head; and let the tears flow. For those few minutes, Max was with me; and yet I was alone with Martin’s beautiful, heartfelt, heart-probing rendition. We three had met at one of those glistening, memorable moments. And the globe paused on its axis.

The subsequent applause was, therefore, quite a shock. It turns out that I was surrounded by many, many others – also rapt, I think.

¶

We were all there – in Northampton High School (with its fantastic setting and facilities) – for a superbly-programmed (and yet free!) concert involving a wonderful conjunction of forces: not only OOTS; but the school’s Senior Orchestra; Senior Choir; Junior School Choir; and Ladies’ Chamber Choir.

This concert is… an amazing opportunity for our girls to work and perform with one of the top chamber orchestras in the country. Nearly one hundred performers from year 6 up to Sixth Form and including our Ladies’ Chamber Choir will be rehearsing with the Orchestra of the Swan in the afternoon, and then will join them in the concert to perform three choral pieces at the beginning of the programme.

Perhaps you would expect, though, at a free event like this one for the music to be of a lesser quality; for the playing to be a little more (shall we say) relaxed? But with the Orchestra of the Swan the centre around which everything revolved – and in a school where music seems to flow keenly and readily; and the girls wear a constant variety of smiles – of course, everything was as wonderfully accomplished and emotionally affecting as always.

The varied programme began with U2, Coldplay, and John Rutter – the extended forces led with great precision and verve by Joanne Drew, Director of Music. (I do so like a choir that sits and stands on the button!) After being stunned by the “quick fire of youth” that is Edward’s Boys, earlier in the year, last night the proceedings opened with voices wearing “the rose Of youth… from which the world should note Something particular” – that is, who were ‘lit’, ‘way live’, if not quite ‘savage’. (I may be “old and reverend”, but not “too old to learn”, I hope, how to be ‘down with the kids’. Um.) Seriously, they were well wicked.

I do apologize – somewhat (but especially to my older demographic) – for the above, er, slang: but, in a past life, I conducted a prize-winning girls’ choir, and yet I was truly amazed by the evening’s wonderful singing – the purity of tone; the enthusiasm; the cohesiveness; the dynamic control. And there were some sensationally good solos, too!

U2’s I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For – “among the greatest tracks in music history” (and one I am proud to have heard live, nearly thirty years ago…) – especially with its “gospel qualities”, is perfect for such powerful choral work. And yet I could not imagine how on earth the orchestra could replicate The Edge’s matchless guitar playing. Credit must therefore go to arranger Mark Benham for producing something as exhilarating as the original. And, of course, to the choir for giving it their all. Wow. (That the members of OOTS – following on from the lovely hushed opening of the school orchestra – all treated this as an equal to the works that followed, says much about their enthusiasm for education and their delight in joining forces.)

Coldplay’s encomium for lost life, Fix You, has similar yearning characteristics, of course: but here – with amazing maturity – was rendered almost as a religious anthem. Again arranged by Benham, this simply grew in ecstasy; and merged “the boundaries of popular and classical music” perfectly.

We were then treated to John Rutter’s The Lord bless you and keep you – I suppose, in a way, a short transitional work; a benediction that led even more obviously to the music that followed. And here, the choir truly excelled themselves: especially those high notes at the work’s “Amen” climax.

This was as thrilling and rousing an opening to a ‘classical’ concert as I have experienced in a while; and one you might think hard to follow….

¶

I suppose I had been drawn to the event by the variety of the works on offer – a little bit of intrigue, especially with regards to the U2 and Coldplay that opened the evening. But this curiosity was accompanied by a profound and long-lasting love for both Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins (BWV 1043) and Mozart’s Symphony No.29 (K201) – which were to follow after the interval.

First, though, fellow Lancastrian and “celebrated British pianist Martin Roscoe [with] his prodigious technique and authority… customary grace and lucid phrasing” was to play Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.21 (you know, the slow-movement one from Elvira Madigan – which is, as Roscoe rightfully stated, actually quite a boring film…).

I think maybe that’s my favorite melody in the world, but then I always feel that every time I hear a Mozart melody no matter what it is.

– Leonard Bernstein: Young People’s Concert: What Is Classical Music?

Let me get one thing out of the way, here: the orchestra and conducting were great, as you would expect – it’s just that I spent the whole work concentrating on Roscoe’s understated, lustrous illumination of music I believed I knew well. There is something intensely mesmerizing about his insightful mastery; and he made the Yamaha CFX concert grand sing in all registers: revealing new relationships between notes, phrases, chords, scales, echoes of themes. This was never a competition with the orchestra for supremacy, either – the balance was perfect; and, as with all such great musicians, communication between all involved was conspicuous and generous.

I suspect this is as perfect a performance as I will ever experience. There was a purity of thought, of technique, of engagement with the music that transcends any of my clumsy attempts to describe it (that’s for sure…).

That it was followed by the Maxwell Davies encore… – well, what can I say…?

Tears stream down your face

When you lose something you cannot replace

Tears stream down your face and I

Tears stream down your face

I promise you I will learn from my mistakes

Tears stream down your face and I

Lights will guide you home

And ignite your bones

And I will try to fix you

– Coldplay: Fix You

¶

After the interval (a deep gulp of fresh air, and reminiscences with the affable Roscoe), we were down to core OOTS for the Bach. After criticizing Curtis, previously, for not taking the helm for this, tonight it just worked so very, very well. This is probably down to the fact that both soloists are foundational members of the orchestra – and their rapport (as well as their delight) was astounding.

Adding a trio of the school’s talented musicians (two cellists and a viola player) to the ensemble helped give the accompaniment a more continuo-like feel; and enabled Le Page and Leech to soar over it – their close relationship painted plangently with equality and tonality to die for. I so love this work; and last night it fulfilled my heart’s deepest desires. This is as it should be. Impeccable musicianship and emotion.

¶

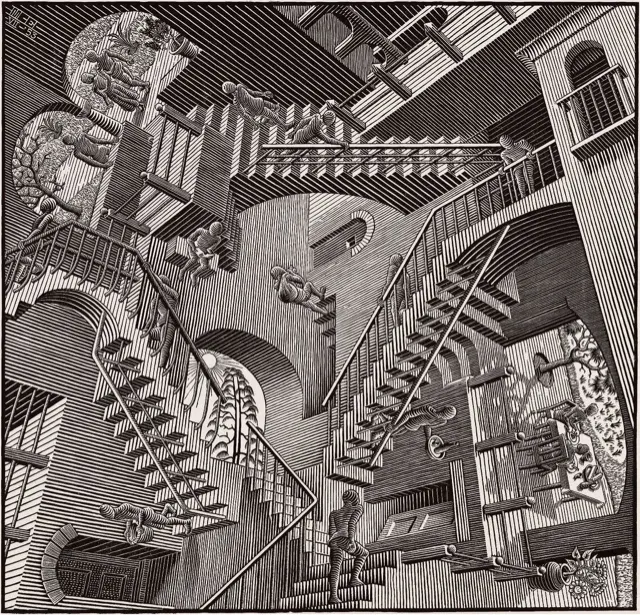

And so it was, too, with my favourite Mozart symphony. I could simply have repeated my earlier review – but with only sixteen musicians on the stage (rejoined by Curtis), somehow yet more magic was conjured. You could follow the line of every single instrument with ease; and yet the melodies floated cohesively into the air, with stunning contrasts of light and shade. (The image that came to mind was what my mum calls “an Edward Seago sky”.)

Special mention must be made, though, of the subtleties and dynamic variations of the self-propelling second movement. Also: the peerless horn playing of Francesca Moore-Bridger and Laeticia Stott. You could tell from Curtis’ generous applause and gentle smirk that even he knew this was so very special… – as was the whole evening….

¶

I may have to stop reviewing OOTS concerts soon: as I have run out of ways to explain and describe their majesty; their translucence; their ability to conquer all the peaks they face; to produce flawless radiance at the drop of a baton. That the forces of Northampton High School meshed so perfectly with them just piled on the amazement. My thanks therefore to every single person involved. I could not have been happier….